In this post, we’ll answer the question: What is tenkara? We’ll start from the basics — what tenkara consists of, and how to actually catch fish with it. Seasoned anglers, please don’t take offense if we look at some things from a beginner’s point of view.

There’s a separate post about why you should try tenkara and what benefits it offers.

“Ask and you shall receive!”

Unknown extortionist (1st century)

About Tenkara

Let’s get straight to it. Tenkara is a style of fixed-line fly fishing that originated more than 400 years ago in the mountain streams of Japan. It was used by professional fishermen for quick and efficient fishing. In many areas, selling fish caught with tenkara was the only source of income for a family. Today, this ancient method has evolved into one of the most modern and minimalist forms of fishing.

For complete beginners — “fixed-line” means there’s no reel. In traditional fishing gear, a long line is wound onto some kind of reel or spool, and the angler releases or retrieves it as needed. In tenkara, however, the line is of fixed length and tied directly to the tip of the rod. Because of this, the line is generally shorter than in other fishing setups, which also shortens the casting distance. But it creates a much more direct connection with the fish — without a reel, you feel every little tug and vibration.

The biggest advantage of tenkara is simplicity. Rod, line, fly — that’s it! This minimalist approach is one of the main reasons why tenkara has gained such worldwide popularity in recent years — that, and its surprising effectiveness.

The word tenkara (テンカラ) originally meant “from heaven”, describing how a trout might perceive a falling insect as a heavenly gift landing before its hungry jaws. These days, even the Japanese themselves aren’t quite sure of the word’s etymology — but that’s fine, as long as it catches fish.

And boy, it does! Tenkara was invented primarily for trout fishing in small and medium-sized streams and mountain rivers that host both smaller salmonids (yamame, iwana, amago) and larger trout (nijimasu, or rainbow trout) in medium-sized rivers, making tenkara a perfect fit for our local waters.

Tenkara spread outside Japan in 2009 and has been gaining popularity ever since. Many spinning and fly fishermen have completely switched to it, while others use it as an additional method for spots that are difficult to reach with conventional tackle. Of course, there are still those who don’t like tenkara and prefer to stick with their old methods — and that’s perfectly fine too.

If you’ve ever wanted to try fly fishing but found it too complicated or expensive, tenkara is an excellent alternative. Simply put, tenkara is fly fishing stripped down to its essentials — everything non-essential has been removed, leaving only the core components.

But if you’ve never even been interested in fly fishing and have no idea what I’m talking about, no worries. Tenkara is intuitive, simple, exciting, and surprisingly effective. It’s a great hobby because it’s not expensive and doesn’t require loads of confusing gear. It’s perfect for complete beginners thanks to its simplicity, yet it can also challenge experienced anglers — because despite its minimalism, it can be developed and refined as far as you like.

What captivates most people about tenkara is its simplicity, functionality, and ease of use. Setting up your rig takes less than a minute, and the casting technique can be learned in just a few minutes. Even a beginner can catch their first fish — be it a roach or a minnow — very quickly.

Unlike with traditional fly fishing, you don’t have to wave the line back and forth in the air multiple times — one good cast is often enough. That means the fly spends more time in the water instead of the air, which is useful since fish live in water too.

A tenkara rod collapses quickly to a compact size. Fully extended, it’s usually between 3 and 4 meters long. What sets it apart from other rods is its lightness and portability — the entire setup typically weighs under 100 grams, making it perfect to bring everywhere, including on hikes and trips.

The Components of Tenkara

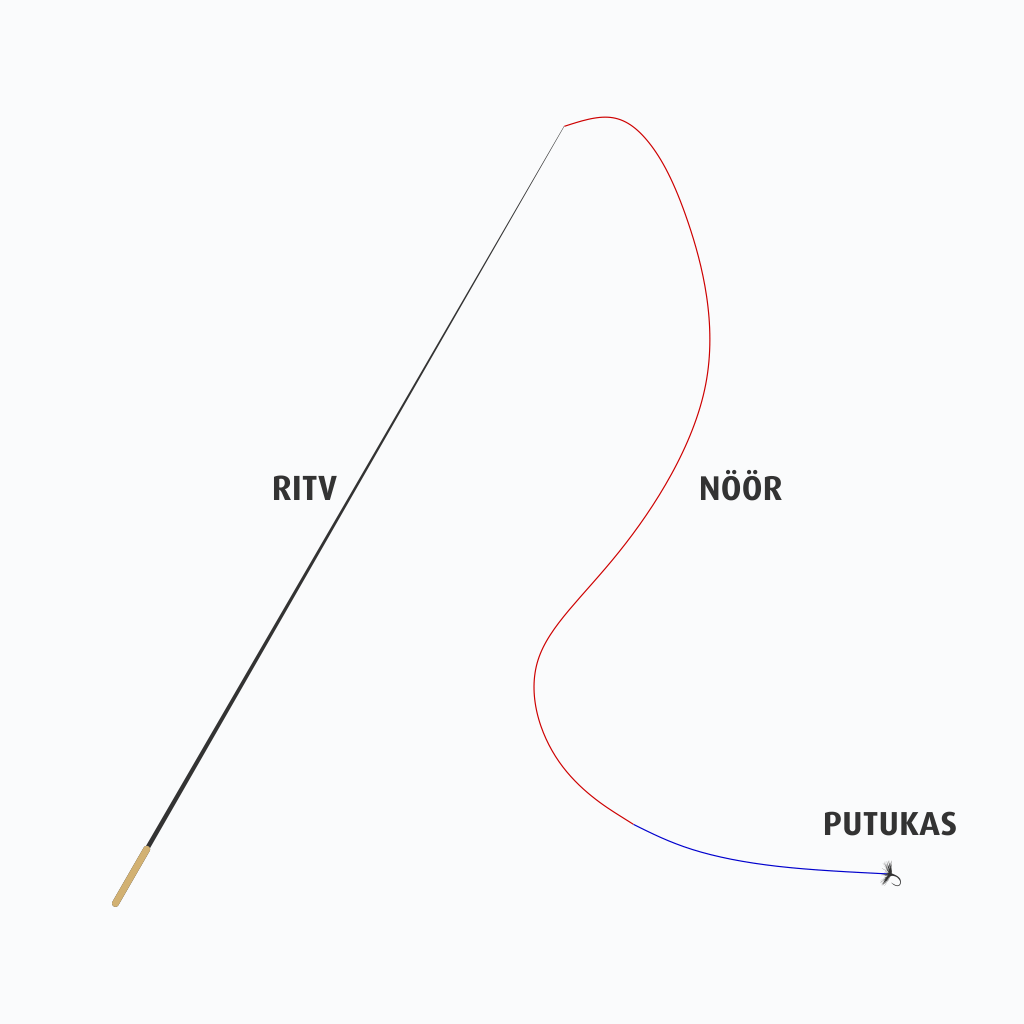

Tenkara consists of just three components:

- the rod

- the line

- the fly

Let’s take a look at each of these components separately.

The Rod

A modern tenkara rod is a long, extremely flexible, and sensitive telescopic carbon-fiber rod designed to cast a very light and thin line. At the tip, there’s a short piece of strong, colored cord called the Lillian, to which the line is attached.

When collapsed, most rods are around 50–60 cm (20″–24″) long, making them easy to carry. Extending or collapsing the rod takes only seconds, so you can start fishing almost instantly. A small tip plug is used to hold the rod sections together when stored. Because the line and fly add almost no weight, the total setup usually weighs under 100 grams.

Rod Length

Since there’s no reel, tenkara rods are typically longer than conventional ones. The average length is 3–4 meters, or about 12 feet, or 365 cm when extended, and 50–60 cm when collapsed. The exact length depends on the type of water and surrounding vegetation — in dense woods, a shorter rod helps to avoid snagging in branches. Like fly fishing, tenkara also requires some space for casting.

Because tenkara first spread out of Japan mainly through the United States, you’ll often see both metric and imperial measurements. A 12-foot rod may also be labeled 360 or 36, all meaning the same thing (3.6 meters). Fortunately, more American-made rods now include metric measurements as well.

Modern technology has also brought us zoom rods — adjustable-length rods that can be extended or shortened depending on your surroundings. These usually have 2–3 usable lengths. Zoom rods are especially useful if you want to fish both in open streams and thick canopies. A great example is the well-known and loved DRAGONtail Tenkara Mizuchi.

The Line

The tenkara line system consists of two parts: the main line and the tippet.

The Main Line

The line is tied to the Lillian at the rod tip. It’s usually brightly colored, so it’s easy to see — the color also serves as a strike indicator. There are two main types of lines to choose from:

- Furled line (braided, multifilament)

- Level line (single-strand, monofilament)

There’s no universal answer as to which is better. Some anglers prefer furled lines, others like level lines, and many use both depending on the situation. According to polls in online forums, the majority slightly favors level lines. As a general rule, beginners find furled lines easier to cast because they’re a bit heavier — but that same weight makes them sag more.

A furled line gradually tapers toward the fly end, while a level line has the same diameter throughout. Level lines are marked with numbers such as 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5 — the higher the number, the thicker and heavier the line. A good all-around choice is size 3.5.

There are also other types of lines, such as PVC floating lines, but they’re less common, so we’ll skip them for now.

For beginners, it’s best to start with a line roughly the same length as your rod, plus the tippet. So a good setup might be:

3.6 m rod + 3.6 m line + 1.2 m tippet.

In the old-school measurement system, that’s:

12′ rod + 12′ line + 4′ tippet.

Once your casting improves, you can start experimenting with slightly longer lines. The general recommendation is to move up gradually, according to the American body-part measurement system — one foot, a larger hand, or whatever bit of manhood increment — roughly 30 cm at a time.

Conversely, if you’re fishing in tight brush, you can shorten the line in the same small increments. Eventually, you’ll find the length that feels most comfortable for fishing in dense vegetation. Most likely, though, you’ll end up using lines of different lengths on different rods: a standard or longer line on a regular rod, and a slightly shorter line on a zoom rod for thickets.

Another big advantage is that, if needed, a shorter line can instantly be swapped out for a longer one. So you don’t necessarily need a separate rod for fishing in bushes or along forest streams.

The Tippet

The tippet is a thin, 0.9–1.5 m (3–5 ft) section of monofilament or fluorocarbon line tied between the main line and the fly. Its purpose is to make the line less visible to fish, serve as a replaceable wear part, and protect the rest of the setup from breaking. When fishing in tight areas with a short rod and line, the tippet can be as short as 0.5–0.6 m (1.5–2 ft).

Typically, a shorter tippet is used with a shorter rod and shorter line when fishing at close range in narrow streams. A shorter tippet also allows you to place the insect more precisely in the desired spot. Start with the longest tippet possible, because it will inevitably get shorter over time — the insect gets caught on a branch, you tie a new one on, the fish breaks the tippet, and so on. When it becomes too short, you can simply tie a new tippet.

When it comes to tippet diameter, there’s also a sizing system. Fly fishers are already familiar with the X-system. The peculiarity of this system is that as the number increases, the tippet diameter actually decreases. So, a 4X tippet is thicker and stronger than a 5X tippet.

Ma ei hakka praegu teid erinevate läbimõõtudega hulluks ajama, vaid tulistan puusalt, et enamasti on kindel laks 5X mõõduga lips. Kui on soov suuremat kala taga ajada, võib kasutada jämedamat, näiteks 4X või isegi 3X lipsu. Kuid kõik sõltub lõpuks ikkagi sellest, millist ritva te kasutate. Paljudel tenkara ritvadel on andmetes kirjas, milline on jämedaim lipsu läbimõõt, mida sellel konkreetsel ridval kasutada võib (ingl k tippet rating). Sellest tuleks ka esmajoones lähtuda ja välja toodud numbrist jämedamat lipsu mitte kasutada, et mitte riskida ridva purunemisega. Lihtne!

I won’t go into all the different diameters right now, but as a rule of thumb, a 5X tippet works most of the time. If you’re targeting bigger fish, you can use a thicker tippet, like 4X or even 3X. Ultimately, it all depends on the rod you’re using. Many tenkara rods specify the thickest tippet they can handle, called tippet rating. You should always follow this guideline and avoid using a tippet thicker than the recommended number to prevent the rod from breaking. Simple!

The Fly

Although tenkara is a fully developed system with its own traditional flies, nobody will fuss if you want to fish with any fly you like. There’s no law saying you can’t bend the rules. The advantages of reelless fishing apply no matter which fly you use. That said, for the best results in tenkara, there’s usually a special fly that goes along with it — the sakasa kebari.

Sakasa Kebari

The sakasa kebari (Japanese sakasa = inverted/reversed, kebari = fly) is a secret weapon in tenkara fishing, as it eliminates the need to juggle different types of flies. Unlike most Western flies, the hackle (the feather wrapped around the hook) on a traditional Japanese kebari points forward, towards the hook eye, rather than towards the hook bend or elsewhere.

Paired with a tenkara rod, this fly allows you to mimic the movements of a living insect on the water. The forward-facing fibers open and close, creating a pulsating motion that drives trout wild.

The kebari doesn’t imitate a specific insect species. Instead, it attracts fish with its natural appearance and subtle movement. Because of this, you don’t have to change it often — sometimes a new fly is only tied on after leaving the old one dangling from a branch. This is perfect for those who aren’t keen on constantly switching flies.

In addition to store-bought flies, kebari can also be easily tied by hand. All you need is a hook, a feather, and some thread. You can even tie one on the riverbank if necessary, though most anglers prefer to prepare them at home using a fly tying vise.

* * *

As you can see, tenkara gear is minimal and straightforward. Some brands, like DRAGONtail Tenkara, make it convenient by offering a starter kit that includes the rod, a line, a tippet, and a few flies — all perfectly matched. This way, you get everything you need at once without overthinking purchases, and it’s often more cost-effective.

Tenkara Fishing Technique

The core principle of tenkara is simple: cast the fly where the fish are likely to be and let the current carry it to them. It’s a method that we, humans, have conveniently learned from fish themselves.

Fishing with tenkara relies heavily on keeping the line out of the water. Ideally, only the fly and a small portion of the tippet should touch the water. This prevents the current from dragging the line, which would disrupt the natural drift of the fly. It also makes the line less visible to fish, increasing your chances of a strike.

Tenkara rods aren’t just long to reach further. Another critical reason is that a long rod allows you to keep the line above water, disturbing the surface as little as possible — a tactical advantage. A flopping line in the water is never helpful when trout are picky. With tenkara, you can cast so that the fly lands first — the “fly first” casting — mimicking an insect falling naturally onto the water.

Of course, keeping the line above water isn’t a strict rule. Rules are meant to be broken, and you can fish however you like. It’s just good to know that with tenkara, it’s possible to minimize disturbing the water.

Movement

When moving along the bank, try to stay as inconspicuous as possible. Trout are alert and can see and hear extremely well. Avoid casting your own shadow over areas where fish may be, and watch your steps — trout can feel vibrations from the bank. Camouflage or earth-toned clothing and stealthy movement are beneficial. Trout fishing isn’t casual fishing — it’s a hunt.

You can also wade in the river when bank access is difficult. Personally, I try to avoid wading to protect the riverbed, stay less noticeable to fish, and disturb the water as little as possible. As old Japanese tenkara masters say: Stay out of the water! Childhood fishing experiences have also set a mental barrier — if I want to chase fish in waist-deep water, a dragnet is usually a better tool. But that is only my opinion, and sometimes I still need to wade.

With tenkara, you can move up or downstream. Upstream fishing can be stealthier because fish are facing the current. Casting upstream is slightly easier without a reel since you only need to let the line out by lowering the rod as the fly drifts downstream. You can also use the river’s slope to create a sharper angle between you and the fish, making you harder to spot.

Tenkara can be fast and mobile, much like spin fishing: cast, move, and cast again. But it can also be used stationary for catching roach or other species. The choice is yours.

Casting

When moving along a trout stream, three casts in one spot, letting the fly drift for about three seconds each time, is usually enough to see if fish are present and interested. Fish often strike within the first three seconds. This is just a guideline — your pace can vary, and the best rhythm comes with practice.

Hold the rod with one hand, either from the handle, the middle, or even the rod blank itself. Place your index finger on top, pointing toward the rod tip. This is not mystical advice, just basic mechanics. This grip prevents the rod from moving too far back during the casting motion. Keep your elbow close to your body and only move your wrist moderately.

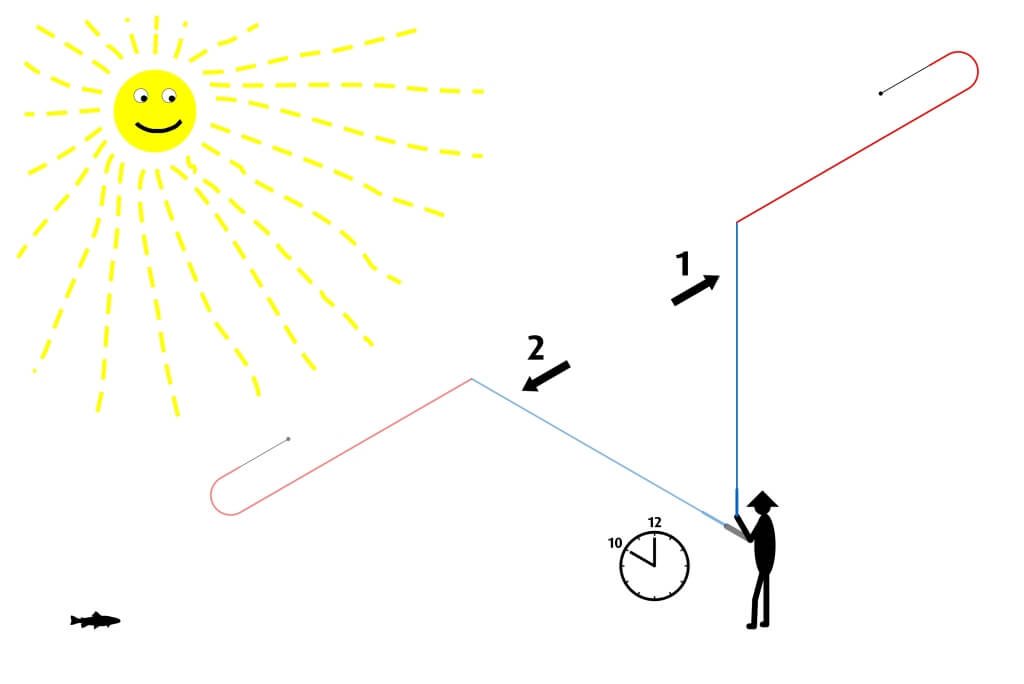

For the classic tenkara cast, hold the rod in front of you. Move it rapidly back until it’s vertical (like 12 o’clock) for the backcast, wait for the line to load, then cast it forward, stopping around 10 o’clock.

For those who didn’t follow that, you can enjoy this very beautiful digital painting, inspired by neoclassicism: a lonely tenkara enthusiast fishing in a scenic river bend on a sunny summer day, with missing palms due to a childhood trauma, casts a fly directly in front of a trout. Everyone else is free to skip this piece of art.

Did you get that? The rod moves between the 12 and 10 o’clock positions.

If there’s an obstacle overhead, like a tree canopy or bushes, you can perform the same cast from either side, keeping the line parallel to the water surface. We won’t add a separate digital illustration for this right now—no need to cast pearls before swine.

In tighter situations, such as between trees and bushes where a standard cast isn’t possible, you can use a “bow-and-arrow cast.” With your free hand, grab the tippet or the hook of the kebari, pull it tight, aim the rod precisely at the spot where you want the fly to go, and release. The kebari will fly like an arrow from a bow, hopefully landing exactly where intended. This type of bush fishing is really exciting, and there’s even a rod specifically designed for it.

Presentation

Presentation, or the way you serve the fly to the fish, starts with the fly landing on the water and ends with its retrieval. How you present the fly can sometimes determine the success of your fishing.

There are several presentation techniques, but the main ones are:

- Dead drift – let the kebari drift naturally with the current, guiding it subtly with the rod tip

- Pulsating – same as above, but add gentle up-and-down movements with the rod tip to imitate a struggling or drifting insect

When done correctly, the fish should strike the delicacy you offer.

Hooking

The fish’s strike is indicated by unusual behavior of the line or fly. For example, the tip of the line or the fly might change direction, stop moving, or the fish may flash its mouth or splash the surface while taking the fly.

Now it’s time to set the hook. Don’t waste time—if a trout senses it’s being fooled with an artificial fly, it will spit it out without hesitation. Make a short, sharp hook-set and hope the fish stays on the hook. As a helpful tip, consider your surrounding natural obstacles. A too-forceful hook-set could send the fly onto a tree behind you, which might be frustrating to retrieve. So when fishing in dense brush, it’s safer to aim your hook-set toward an open space.

Playing the Fish

If a smaller fish strikes, which doesn’t resist that much, it can be taken out without much effort. Larger fish, however, usually need to be tired out first to reduce the risk of escape or breaking your tackle.

The key is to let the rod do most of the work. A tenkara rod is designed for this—flexible and strong. Lift the rod tip up or to your side and let the fish pull the rod into a proper bend. Your tenkara rod is built to absorb the fish’s runs, and it works best when held at roughly a right angle to the line.

Do not give in too much to the fish or let it pull the rod straight. If you do, the rod’s bend won’t work, all the stress falls on the line, and the tippet—the weakest part—will break first. In that case, you’ve lost your trophy.

When playing the fish, try to guide it to calmer water; fast currents make fighting more difficult. Try to avoid logs and other obstacles where the fish might tangle and escape.

Väike abistav nipp on nööri tõmbesuuna muutmise abil kala suunamine endale soovitud suunas. Kuna kala punnib nööri tõmbesuunale täpselt vastu, saab tõmbesuunda muuta vastupidiseks selle suunaga, kuhu kala soovitakse juhtida. Ma ei tea, kes keegi sellest seletusest aru ka sai, aga nii see põhimõtteliselt töötab – kala liigub nööri tõmbesuunale enamasti vastupidises suunas.

A small trick is to change the line’s pulling direction to guide the fish where you want it. Because the fish resists the pull, reversing the pull can steer it toward your desired direction. I’m not sure how many of you understood that explanation, but that’s basically how it works—the fish usually moves in the opposite direction of the line pull.

Landing the Fish

Once the fish has tired enough and no longer fights, it’s time to take it out of the water. Raise the rod tip with one hand and hold the fishing line with the other. Then smoothly bring the fish toward you, wet your hand, and grasp it gently but firmly. Avoid injuring the fish or handling it with dry hands.

Even better, if you have a landing net, you can retrieve and release the fish without touching it at all. Handling a fish with dry hands risks damaging its mucous layer, reducing its survival chances by anywhere from one-fifth to half. Of course, if you plan to keep the fish for food, it matters less, though it’s still best to minimize suffering.

If you want to humanely end the fish’s life while preserving maximum meat quality—and feel like a tenkara ninja—you can use the traditional Japanese fish-killing technique called ikejime. Though it may look a bit uncanny at first, it instantly disables the central nervous system and prevents rigor mortis, resulting in perfectly clean-tasting, high-quality meat.

We hereby encourage you to practice C&R (catch and release), as it’s the foundation of modern sport fishing and crucial for preventing overfishing.

Video

There’s a great overview video where Daniel Galhardo—the man who first imported tenkara from Japan to the USA in 2009—demonstrates this fishing method.

Similar Fishing Styles

Tenkara isn’t the only fishing style of its kind. In northern Italy, a very similar technique called valsesiana developed entirely independently of tenkara. Below is a short film showing a valsesiana grandmaster practicing this style.

Beautiful, eh? But as always, the Russians don’t want to fall behind either. Here’s an example of their style:

Summary

This was a brief introduction to the essence of tenkara. We will continue with this series about tenkara and write some separate, more detailed posts on certain topics.

If reading this post has sparked an urge to get your own tenkara gear and try the method, DRAGONtail Tenkara is the place to get everything you need quickly and at a reasonable price. Still, it wouldn’t hurt to do a little research first to decide which tenkara rod to choose.